Omezue, the Complete Achiever

Volume One of the Victims Series

Ugo Agada-Uyah

ENDORSEMENTS

“Omezue, the Complete Achiever follows the transatlantic slave trade as it blazes its destructive trail across Igbo land … Ugo, in this epic story of a people’s struggle for survival, the first in the Victims series, combines the otherworldliness of The Lord of the Rings with the fast-paced, action-adventure historical fiction style of Conn Iggulden, thoroughly meshed together with her deep, incisive knowledge of the cultures of her people that make her novel absolutely interesting as she propels you along the twists and turns of a tightly plotted theme, sub themes, plausible characters, intrigues, danger, suspense, and deep-seated resentments that keeps you turning the pages.”

—Professor Hyginus Ekwuazi, multiple–award winning poet and nominee, Nigeria Literature Prize

“Ugo Agada-Uyah’s debut novel, Omezue, the Complete Achiever, is a must read for those searching for a true African story that examines the roots of our sociopolitical problems in modern times. She is preoccupied with her favorite themes—search for good leadership; a people’s struggle for justice, equity, and fair play … situated in the rich African, Igbo cultural setting of the southeastern part of Nigeria … The story engages your imagination through the use of simple but evocative language, symbols, imageries, and rich African, Igbo proverbs. Reading the book becomes a wonderful experience in appreciation of the very critical but creative mind of the author. In all, another great creative work … a must read for all.”

—Professor Ahmed Yerima, chair, Department of Visual And Performing Arts, Kwara State University, Malete

“In this gripping story of a family’s quest to exorcise an oracular death curse, Ugo, in Omezue, the Complete Achiever, captures vividly the intrinsic values and essence of her people’s worldview, imbedded in the omume title—its emphasis on the sacredness of the responsibilities imposed on leaders by the gods, of moral uprightness, of bravery and heroic deeds … and answered the often asked question—where did the slaves come from? This is their noble heritage!”

—Omezue Anthony Ogbonnia Ekoh, member of the order of the federal republic (mfr).

“Achebe’s fans will love this! … Ugo, a retired federal director of culture turned writer, debuts with this wonderfully crafted, meticulously researched page turner, Omezue, the Complete Achiever … a brilliant depiction of the horrors of the slave trade era—the insecurity, the suffering, the brutality, and the devastation that characterized that inhuman trade … superbly woven into the fabric of the ancient cultures of her people … taking you on a breathtaking, suspenseful, action-packed journey through the ancient worlds of her people in which she’s an authority … She grabs and holds you from the first page, immersing you in the lives of the characters—their fears, their pains, their joys—till you turn the last page … that leaves you looking forward to the next in the series. Be warned! Don’t start this book if you have urgent things to do—you can’t put it down!”

—Nkanta George Ufot, federal director of culture, Abuja, Nigeria

Omezue, the Complete Achiever

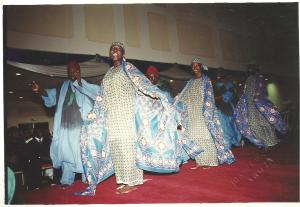

Volume one of Victims series is set in mid-nineteenth-century Igbo land, situated in the southeastern part of Nigeria, spanning from the small, ancient, culturally rich city-state of Uwa, across the slave trade–ravaged Igbo hinterlands, to the land of the powerful oracle—the All-Knowing God of Ako Kingdom, whose people dominated the affairs of Igbo land throughout the slave trade era.

However, despite its historical background, Omezue, the Complete Achiever is not a history book. It is a novel. According to historians, many of the novel’s events did occur—like the havoc the transatlantic slave trade wreaked across Igbo land in particular and Africa in general, as well as the role powerful nineteenth-century oracles of Igbo land played in the slave trade. But for privacy, the name of the city-state, ‘Uwa,’ the legendary founder of Uwa, ‘Isiali,’ the name of the oracle, ‘All-Knowing God,’ and the great slave markets have not been accurately named.

Apart from these changes, I have juggled with history to suit my own reality—rearranging Igbo land, taking interesting incidents from history, and creating peoples that I hope will appear very real to you but who are actually all products of my imagination, and no reference to anyone that was or is part of Igbo land is intended—for this book is fiction! All characters in it are therefore fictitious, and any resemblance to real persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

2013 iUniverse Paperback Edition

Copyright© 2013 by Ugo Agada-Uyah

All rights reserved.

Published in United States by iUniverse

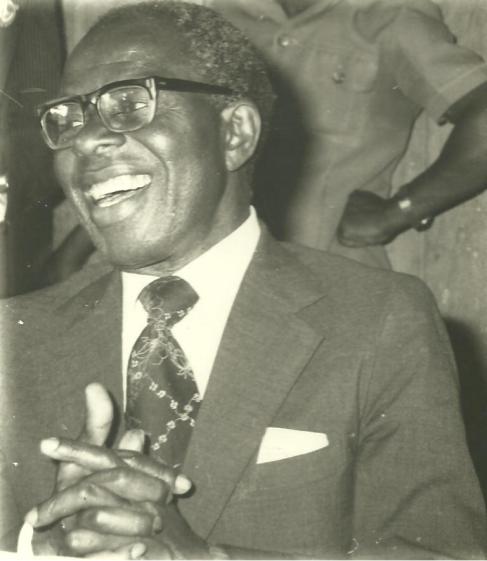

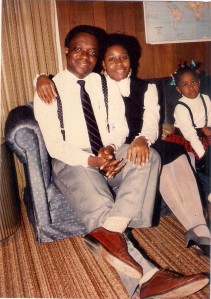

To Papa,

fount of my inspiration

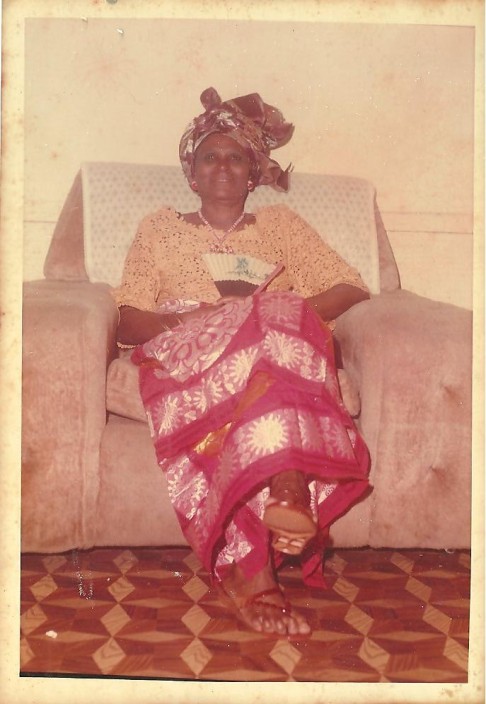

To Mama,

model of Afikpo womanhood

Acknowledgments

A number of people have made enormous sacrifices of their time, energy, and facilities to make this book possible. I can’t name them all, but there are people I can’t help but mention. I thank my late father, Omezue Nnali Mbe Agada, who taught me to appreciate the value of my culture and heritage, which today is the fount of my inspiration; my late mother, Odoziaku Ude Eke Agada, whose life was a model of Afikpo womanhood; my late brother Chief Michael Ikoro Mbe Agada, Oderi Oha I of Afikpo, for his incisive comments on the manuscript; and my late brother Mazi Dominic Mbe Agada, who died on July 23, 2012. Brother, you never tired of answering my numerous questions at all hours of the day. That you didn’t live to see the book in print is my greatest sorrow.

Special thanks to my literary mentors—Chief and Lolo Enyinna Igbokwe, for having had the courage to wade through my first-ever manuscript and, since then, for having guided me to where I am today; to Honorable (Colonel.) and Chief (Mrs.) Tunde Akogun (retired), for their faith in my literary ability and for their support during the staging of my very first play at the National Theatre, Iganmu, Lagos, in 1985.

Ajibade, I can’t thank you enough—ever! Without you, this manuscript would never have been typed.

Dr. Austin and Ngozi Eleje and Mr. Idu Okogeri, how do I thank you and your beautiful families for being there for me when I was in the United States? Thanks for your patience with my unearthly hours during my stay with you and your unwavering belief in me.

Thanks to my beloved sister Ugo Law and her wonderful husband, Inya Fidelis Nnachi of EmmaFids & Associates, whose steadfast love and faith in my ability sustained me throughout the publishing process.

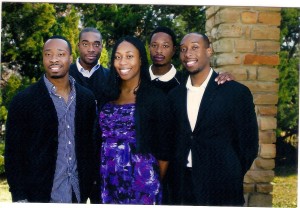

To my children—Ihuoma, Ude, and Ugo Uyah and my other numerous children, both biological and acquired, thanks a million times for just being there for me.

The wonderful team at iUniverse—thanks for making a published author of me at my age—sixty-four! Abajokwagim!

Unu jokwa … Thank you all!

Prologue: The Boats Arrive

Inside the obu, the ancestral temple house of Otutu village, not a cough betrayed the presence of over a hundred elders, who sat in grim silence with dread in their eyes and fear in their hearts as they waited.

The atmosphere inside the obu was tense, very tense.

They sat hunched forward, leaning on their walking sticks—their staffs of office—listening and waiting.

That morning, fishermen returning home from night fishing had brought disturbing news: danger threatened! The alarm horns had sounded immediately, alerting the entire city-state of Uwa, summoning her braves to arms. Members of Eto age grade, the armed forces of the city-state, had been dispatched at once to the river to check the validity of the fishermen’s claims regarding what they had seen.

And the elders were now waiting anxiously for their return.

Let the visitors just be passing through, the elders prayed silently as they waited under the watchful eyes of their revered ancestors, hoping for good news from Eto.

On a slightly raised platform that faced the rest of the assembled men, three men sat on beautifully carved wooden stools. Essa Okaomie sat in the middle; he was the spokesman of Essa age grade—the legislative, administrative, and judiciary arm of Uwa government. He sat hunched like the rest, surrounded by an aura of wisdom and power that even the anxiety in his piercing grayish-black eyes could not diminish.

To Okaomie’s right sat Onikara Isiego, the chief priest of Nkpurukem—the bee goddess—and the spokesman of Onikara age grade, the advisory age grade to Essa. He was about eighty, of average height, dark complexioned, with a mop of white hair and shrewd brown eyes that under normal circumstances would have had a twinkle lurking somewhere in their depths. But there was none there now. His eyes were grave and troubled.

Horii Ugwu, Eleri, the yam priest of the entire city-state, sat on the stool at Okaomie’s left. He was the spokesman of Horii age grade—eaters’ age grade. He was ancient, over a hundred. He looked old and fragile; his rheumatic eyes staring at nothing, his worried expression mirroring the general sense of unease and foreboding that pervaded the state.

Toward dusk, near the obu, a dog growled. The elders inside turned toward the sound of rapidly approaching footsteps. Three heavily armed men drenched in sweat came into view and hurried into the obu. They were members of Otutu executive age grade.

The elders searched their faces for any sign of hope. There was none. Their faces were as grim as those of the elders waiting in the obu.

“Oha m unu ka,” Agu greeted. He was Okaomie’s junior brother and the spokesman of Eto age grade in Otutu village group.

There was no response from the elders; none was expected. His greeting was mere formality to secure their permission to speak. Their only response to his greeting was that each of them sat up straighter on his stool and became more alert.

“We saw the two strange boats the fishermen reported this morning, anchored off our shores in deep waters. This evening, another joined them as we watched. There were white men on the deck of each boat.” Agu briefed them quickly, as he and the men with him were expected to go back to the beach and await further development. The urgency in his voice and the gravity of his countenance communicated themselves to the elders.

On the face of every elder, only consternation, apprehension, and fear could be discerned. At first, they sat there paralyzed with terror, and they were men who did not scare easily. They were warriors—all! But they had seen the havoc the slave trade had wreaked on other Igbo city-states and were petrified of the same thing happening to Uwa.

“Obasi no na elu-e-e … Great Spirit on High, the iniquitous trade has finally reached our shores!” Essa Okaomie cried in horror. “Our ancestors, where are you? Give us strength to protect our children, we implore you. Help us to save them from falling victim to this rapacious trade that has blazed its destructive trail across our land, devastating and ravaging all in its path, wrenching our children from their homeland—men and women in their primes of life—and carting them away into slavery,” Okaomie prayed, recognizing at once the menace the boats posed to the city-state and especially to its children.

He looked down on the faces of the other elders that stared up at him with trepidation and asked in a voice that was firm and strong, “What do we do?”

With that question, the initial fear that had clutched them in its clammy fingers was thrown off, and their visages became resolute and determined to defend their land and their loved ones.

“Those boats are harbingers of death,” Onikara Isiego said vehemently, casting a fierce glance at the other elders, daring them to be anything but strong. “Be sure of this: the moment their presence in our waters is known to the slave merchants, kidnappers and slave raiders are going to start showing their ugly faces here in Uwa. To combat that menace, the advisory age grade wishes to advise that from now on, the executive age grade and the youth age set should work out a schedule to police our boundaries at all times.”

The other elders nodded their heads in agreement.

“The situation is grave, very grave. The scourge has finally reached us. Our lives are not safe anymore,” Horii Ugwu said in a shaky voice. “Horii seconds Onikara’s advice but adds that, from this moment, Uwa should declare a state of emergency.”

“So be it!” Essa Okaomie pronounced, thus signing the decision into law with the legislators’ acceptance of the advice given by the advisory age grade and seconded by the eaters’ age grade. “Eto, henceforth, all strange persons must be apprehended and brought to Essa.”

From that moment, the entire city-state went on alert.

Part 1

The skies were overcast,

The storm clouds gathered,

Waves of death overshadowed the land,

Torrents of destruction assailed it,

Scavengers hovered!

The omniscient gods foresaw it,

Distressed by the magnitude of the impending catastrophe,

Appalled by the ravages of the all encompassing evil,

The bloodbath, the holocaust, the grim harvest,

The gods cried out!

Mother Earth wept!

But men, blinded by greed heeded them not

And plunged the land into depths of human degradation,

The iniquitous trade—trafficking in human beings

As mere commodities!

Tufia!

—A dirge, Ugo Agada-Uyah

Chapter 1

Four days after the arrival of the slave boats, Okoro, a ruthless slave merchant from AkoKingdom, stood on top of the sharp, rocky sandstone ridge of considerable extent that marked the boundary between Uwa and other Igbo city-states. His hard, cold eyes stared down into the prairie trough of a syncline below, encased within undulating waves of sandstone ridges. His smoldering brown eyes were alert as they surveyed all around him, taking in his surroundings.

Satisfied there was no other person within the vicinity, he trudged wearily down the hill toward the valley. The early morning air was chilly. Fog still hung over the land, and the wind that whistled past him as it swept down into the valley was cold. He looked up into the sky—it was frowning. The clouds were gathering, and a serious storm was brewing. A storm had been raging when he left AkoKingdom three days ago, and it had not abated throughout the journey.

The trip should have taken him longer, but he had set himself a murderous pace. He hoped to be the first Ako man to lay territorial claim to Uwa city-state as a sphere of influence for his village. It was an act that would accord his village the exclusive right to deal with Uwa commercially and religiously, on behalf of his priest king, Eze Ako of Ako Kingdom.

At the thought of the diplomatic skirmishes that would follow, a smile flitted across his tired face.

I’ve yet to see my match in diplomatic fencing, he thought arrogantly, smiling again.

Lightning slashed across the sky; he quickened his pace. At the valley that marked the base of the trough, he came to a crossroads; high, rocky ridges dwarfed him on all sides. He hesitated, wondering which way to go as thunder rumbled after the lightning that sent animals scurrying for cover. The cold wind seeped through his long robes into his body. He shivered and looked up into the sky at the gathering storm.

I wonder if the storm will hold off. I have to find shelter quickly, he thought anxiously.

His tired eyes swept over the open prairies, surveying the land with a conqueror’s eyes—there was no habitation anywhere. To his right, a dense forest backed up against a steep limestone bluff that was sticking out in the middle of the open grassland like a sore thumb.

Uwa is a lovely country, he mused. How appropriate that Uwa, established by an Isi son five or six generations ago, should be colonized by an Isi son now, he thought and laughed out loud, sending birds fluttering into the darkening sky at the sound of his harsh, grating voice.

Then he froze, the laughter dying in his throat.

He looked round swiftly and saw nobody. Lightning slashed across the sky again. Thunder rumbled overhead, and the wind wailed all around him. He didn’t heed any of it. His ears had caught a strange sound—the cry of babies in that desolate place with no habitation around.

Then he heard an ominous sound—the growl of a predator. It came from the forest. The frantic cry of babies came again, now intensified with dread. His hand went to the hilt of his sword. Silently, he slipped it from its sheath. Storm and shelter were forgotten. His entire attention reverted to the forest and its strange inhabitants.

Is the beast going after the babies or me? Okoro wondered.

He stood rooted where he was, alert and ready, sweat raining down his face. The cries and the growls were coming from the thickest part of the forest. He stared into the forest, straining in vain to see through the thick undergrowth.

The guttural, threatening sound of the beast became a continuous rumble as it moved through the forest. Okoro could hear dry sticks snap under the beast’s weight as it padded leisurely toward its prey. From its heavy tread, he knew it must be a huge animal.

A lion, maybe, he thought.

Then it pounced! Abruptly, the voice of a baby was silenced. The act had been preceded by a deep, throaty growl that sent shivers spiraling up and down his spine. The earth shook with it. That confirmed it for him.

That growl can only come from a lion, he told himself.

He tightened his grip on his sword hilt. His fingers shook slightly as he stared fixedly into the forest where the last growl had come from. He strained to listen to the beast, but he couldn’t block out the pathetic cry of the remaining baby, which had became a heartrending, terrified shriek calling for help that, alas, would never come. The cries were accompanied by the sound of the beast gnawing the delicate bones of its first victim, followed by satisfied growls. He stood transfixed where he was, unable to turn his back on the threat posed by the savage animal in the forest.

“Who are you?”

Okoro jumped and turned around swiftly toward the source of the question. A man stood at a safe distance with a drawn hatchet, watching him warily.

The man was Eto Agu, the spokesman of Otutu executive age grade. Okoro hadn’t heard him approach. He had been totally engrossed in the macabre events taking place in the forest.

Face to face with Okoro, Agu took a startled step backward. He immediately recognized Okoro for what he was—an Ako man. The insolent air that surrounded him proclaimed him so. That suspicion was reinforced by his fine physique that was still evident despite his haggard face and bloodshot eyes, consequences of his harrowing three-day journey.

That Okoro was handsome, there was no doubt—with his delicately molded, finely etched nose that flared with fatigue—he was a good specimen of his tribe. He was of lighter complexion than the average Uwa man. The head he cocked condescendingly to one side to survey Agu was well sculpted. As he straightened up to his full height, Agu saw that he was inordinately tall. He was, in fact, a giant of a man.

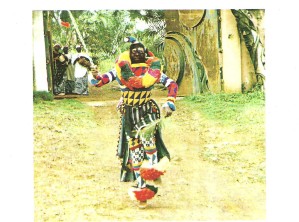

But it wasn’t his splendid physique that held Agu rooted where he stood in shock. Rather, his stunned eyes had been drawn to the long, red cap that was pulled down to shield his ears against the early morning chill and the staff he held in his left hand, both of which were insignias of office of highly titled men. The rare loincloth he wore, ukara, identified him as a member of the dreaded Ekpe—Ako secret society, the law enforcement arm of Ako Kingdom. It was the equivalent of the executive arm of Uwa government. Agu knew that only members of that powerful society would dare wear the ukara loincloth with such casual swagger, even away from Ako Kingdom. The ukara was a beautiful fabric made of Ekpe secret society textile material, of batik print, dyed with indigo, and replete with numerous Nsibidi secret symbols. It was tied round Okoro’s waist to fall in graceful folds around his ankles. Over it, he wore a big robe.

As he stood there in his towering height, with the long, naked sword of the finest workmanship in his right hand, he looked every inch the proud aristocrat he was, from the most powerful kingdom in Igbo land. His stance was calculated to be haughty and intimidating.

He’s not only a highly titled man but a very wealthy one too, Agu thought, his mind spinning with foreboding. What’s such a distinguished Ako man doing so far from home and within Uwa territory at this point in time? he asked himself. With that question came terror as a more disturbing one flashed across his mind—On the heels of the three slave boats?

Agu shuddered to think of the implications of such a coincidence because since the white man’s insatiable demand for slaves had started, the sight of their slave boats anywhere spelled doom for nearby communities. The presence of Ako men who were their partners was even more dreaded.

Okoro surveyed Agu disdainfully, with his nose stuck up in the air. So that apart from his age and affluent looks, his attitude made Agu suspect at once that he must be three of the most hated things in Igbo land rolled into one—a slave merchant, a shrine envoy, and an emissary of the priest king of Ako Kingdom. “Tufia!” Agu exclaimed silently in his mind, now thoroughly alarmed.

“What’s the name of this place?” Okoro asked insolently, ignoring Agu’s question as to who he was. His shrewd, intelligent eyes had noted the fleeting expressions that warred across Agu’s face. He did not miss the dismay and panic on Agu’s face as recognition dawned. He had also seen the significance of his attire register on Agu’s face, and contempt flashed across his countenance before his diplomatic shutters came crashing into place and his face became guarded and unreadable again—an Ako trademark.

But Agu, who was watching him closely, had seen that scornful look flash across his face. There was no doubt in his mind then that Okoro was what he suspected him to be. He could discern his sharp wits hidden behind his silent, watchful eyes and the conceit, heightened by the unapproachable, standoffish, don’t-touch-me air that surrounded him.

Agu’s reaction to that implied snobbery was swift. His hackles rose, and his temper bristled. What Okoro didn’t know was that an Uwa man had an innate pride that was his intrinsic makeup which didn’t take kindly to bullying and that he did not succumb docilely to any form of foreign domination. He would prefer to die than live under such a situation.

“The evil forest,” he snapped.

“What of the babies crying inside the forest?” Okoro asked softly, his head cocked to one side, and again saucily ignoring the question.

Agu’s anger reared its head, menace crept into his countenance, and his eyes hardened. His voice sharpened as he repeated his earlier question, watching Okoro closely all the time.

“Now, who are you? I won’t ask a third time,” he grated through clenched teeth, his hand tight on the head of his hatchet.

Okoro recognized the dangerous edge that had crept into Agu’s voice and the meaning of those fingers that tightened on the head of his hatchet. Okoro knew that he was only a hair’s breadth from being killed.

“I come from the old homeland, Ako Kingdom,” he replied quietly, watching Agu closely.

Loud cracking came from the forest.

They both jumped, startled, thus reminded of the immediate danger a breath away.

“The babies are twins,” Agu bit out. “You’re an Igbo man. You should know they’re considered abominations and are thrown away into the evil forest at birth.”

As he spoke, the beast finished feeding and padded away leisurely, leaving the remaining baby shrieking in terror.

Now that the threat in the forest was gone, Okoro turned his full attention to Agu and took stock of him. He saw a man in his early fifties, almost as tall as himself, well muscled and physically energetic. He was clean shaven, with a hint of a cleft at the tip of his firm chin, and he had a head and chest—now heaving with suppressed anger—covered with charcoal-black, woolly hair. A big nose dominated his face, and laughter lines crisscrossed his tautly pressed mouth. The grayish-black eyes that bored into Okoro were steely and sparkled with the fury he was barely able to hold back. The charge of vitality emanating from him at that moment would’ve intimidated a less courageous man faced with his drawn hatchet and towering anger—but not Okoro, who knew that his Ako heritage accorded him an immunity that Agu could only ignore to his peril and that of his loved ones. City-states had been wiped out for merely insulting an Ako man.

“What are you doing so far from home and alone in these dangerous times?” Agu rasped out.

“Is this Uwa, the city-state founded by Isiali, who left Isi village in AkoKingdom about five or six generations ago?” Okoro asked quietly.

“Do you always ignore questions? What are you doing so far from home and alone?” Agu barked, now thoroughly irritated by Okoro’s impudence and disrespect by ignoring his questions. His patience was fraying quickly. He shifted the hoe slung over his left shoulder to a more comfortable position. From his dress, it was obvious he was on his way to the farm. His towel loincloth was wrapped around his waist, passed between his legs, and fastened at his back.

“If this is Uwa city-state, I’ve come to obtain the elders’ permission to settle,” was the quiet reply.

There it was!

It was as Agu had feared: Okoro was the priest king’s envoy—a settler! It was the most frightening statement every Igbo community prayed never to hear from an Ako man. Terror gripped him as cold sweat broke out all over his body.

Danger! the warrior in him screamed, and the adrenaline surged in him, urging him to take action. The scourge, as Horii Ugwu had said, has finally reached us. What to do? Kill the pest to save Uwa? he asked himself frantically. Our ancestors, where are you? Help!

Okoro’s face was expressionless as he watched him, but he was taut and alert. He had seen Agu’s face harden into a warrior’s implacable visage and also the temptation to kill him that had flashed across it. He had no illusion he would be a match to Agu in hand-to-hand combat. He was no warrior, while the man before him was obviously a professional. All the same, his fingers gripped the hilt of his sword more tightly, in readiness for a fight.

At least I’ll be able to inflict some harm before my death, he thought as he stood unflinchingly before Agu. But gradually, he saw the manic look fade from Agu’s eyes as he regained his sanity, and his fingers relaxed their death grip on the head of his hatchet, though Okoro didn’t lessen his vigilance.

He didn’t know that Agu had remembered just in time that the man before him was not only an Ako man but a highly titled one too—most likely an aristocrat. He knew in those dangerous times that only certain groups of individuals were immune from attack wherever they went—Ako men, titled men, or ritual experts like shrine emissaries of powerful oracles. It was an abomination to harm priests and emissaries of strong deities, because any attack on them was considered an act of sacrilege.

He had also remembered the more mundane consideration of “an eye for an eye,” which was the basic principle of all Igbo intergroup relations. And Okoro was not only a highly titled man but an Ako man, which meant that the reprisal for his death would be great.

Most importantly, Agu had remembered Essa’s injunction to Eto, instructing them to report all strange faces to the elders. With that thought in mind, his decision was made.

“This way,” he said abruptly, indicating the way he had come with a wave of his weapon. And with a toss of his head, he invited Okoro to precede him.

He saw something flash briefly in Okoro’s tired eyes, and his own eyes narrowed in thought. It had been so quickly veiled that he couldn’t fathom what it was.

Was it fear or relief? he mused. No, it can’t be fear, because one thing I can bet on is that the man before me isn’t someone who would be easily frightened by a naked hatchet. So it must be relief. Why? he asked himself.

Then he sighed and gave up trying to understand Okoro’s actions. You’ve got to be very careful when dealing with an Ako man, Agu reminded himself. You’ve got to be on your toes, permanently on the alert. They are feared for their wit and craftiness. I’ll leave such things for Okaomie to deal with. He’s as astute a diplomat as any Ako man, Agu thought.

“Where are we going?” Okoro asked cautiously.

“Your fate is not mine to decide,” Agu snapped shortly, at the same time wondering if he was doing the right thing taking an Ako man into Uwa at that crucial moment. But he knew he had no other choice than to take him to the elders.

Let the elders decide whether he should live or die, he cautioned himself, still filled with the temptation to eliminate the man there and then.

Historical Notes

The transatlantic slave trade is often regarded as the first system of globalization. According to French historian Jean-Michel Deveau, the slave trade and consequently slavery, which lasted from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, constitute one of “the greatest tragedies in the history of humanity in terms of scale and duration.” For four long centuries, Africa heaved under the onslaught of the transatlantic slave trade as it blazed its destructive trail across the land. A tragedy described by UNESCO as “one of the greatest dehumanizing enterprises in human history.”

How It All Began

According to Elizabeth Isichei

The first European visitors came to south-eastern Nigeria in 1472, or perhaps slightly later. They were Portuguese, and they came to Nigeria during their attempt to discover a sea route to India. One of these early visitors, the author of a navigator’s guide written in about 1505–8, gives us what is probably the first written description of Igboland: ‘a land of negroes, called Opuu, where there is much pepper, ivory, and some slaves.’ These first European visitors bought ivory, pepper, and locally made textiles, which they sold elsewhere in West Africa. They bought few slaves, because at the time Portugal had little use of slaves. But unfortunately for Igboland, and Africa as a whole, soon after the Portuguese reached south-eastern Nigeria, Columbus discovered some islands off the coast of America. Many other Europeans followed him, and went on to explore central and southern America.

In the New World the Europeans discovered vast potential wealth, both in mineral resources and land. Both sources of wealth needed ample labor for exploitation. The native Indians could not supply it—they died in vast numbers of diseases the Europeans introduced.

So they turned to West Africa, aptly called at the time ‘the Slave Coast.’ In 1518, the first load of African prisoners was taken directly from West Africa to the West Indies, ushering in over four centuries of the infamous triangular trade. As Isichei said, “For the African societies it touched the trade was a disaster. In Igbo land, it spread across the fabric of life like a stain.” It wreaked untold havoc, depopulating the land, destroying her economy, and put her civilization on hold, so that, according to History of West Africa, Book One, the worst consequences of the slave trade was that it “left a psychological legacy of suspicion, servility, or hostility which has been one of the most serious obstacles in Eurafrican relations. Many educated Africans privately believe that the slave trade is the main explanation for their so-called primitiveness … They feel that they were the victims of history, held back while other people were advancing.”

The book also believes that

The most undeniable consequence of this appalling trade was the suffering involved … There are grim accounts of what was involved in slave raiding and slave trading in Mungo Park’s story of his journey with a slave coffle from the Niger to the Gambia in 1796, and in Major Denham’s account of the slave raid which he accompanied on the frontiers of Bornu in 1823, when children were thrown into blazing huts, the age massacred, the wounded destroyed, and the sick left to die.

A possible total of fifteen million people left West Africa as slaves between 1450 and 1860. For every person who left West Africa at least one other died, either massacred in his village or dying on the route to the coast. Those who were sent into slavery were picked because they were young men and women in the prime of life, and their going created a serious deficiency in the population.

The horrors of the trade were faithfully depicted in the annihilation of Onwu’s village, Okaomie’s friend that lived along the route to Ako Kingdom in chapter 15 of Omezue, the Complete Achiever. According to Elizabeth Isichei, “the Slave Trade robbed Igbo land of many of her members in the prime of life and the children they would have had.” To date, the actual number of Igbos sold into slavery can never be fully known because, “for every one that left, at least ten others died either in the massacre that accompanied the raids, or on their way to the coast. And for everyone that reached the New World, three others died in the atrocious Middle Passage.” According to a slave ship captain who made ten voyages to the area between 1786 and 1800, “of the over 20,000 slaves sold annually at Bonny, 16,000 of them were Igbo. Over a period of twenty years,” he claimed, “320,000 Igbos has been sold into slavery at Bonny and 50,000 at Calabar and Kalabari.”

And that tragedy lasted four centuries!

Fortunately, in the first half of nineteenth century the transatlantic slave trade declined. “In 1807 Britain passed legislation forbidding her nationals to engage in slave trade. It did not involve other nationals, nor did it abolish the institution of slavery in British dominion …. The trade lingered longest in Nembe-Brass, where the last slaver called in 1850.”

That Was Around the Time Our Story Began in Uwa

During the slave trade era, there were a people whom I called the Ako people, meaning ‘cunning,’ who dominated the affairs of Igbo land. They were the main slave merchants and middlemen for Europeans. They were the ones who went into the interior to procure slaves. Along the trade routes, they established settlements. The settlers in those settlements acted locally as agents of their oracle. Chapters 1, 2, and 3 of Omezue, the Complete Achiever faithfully described the freedom, the fearlessness, the pride, and often insolence of those people; they were immune to all forms of harm. The name Okoro is a common name among the Igbo peoples of southeastern Nigeria.

As Isichei said, the saying that “Igbo are governed by gods and ancestors” holds true even today, because, “to the Igbo, the secular and the sacred, the natural and the supernatural are a continuum. Supernatural forces continually impinge on life and must be appeased by appropriate prayer and sacrifices,” as we saw throughout Omezue, the Complete Achiever. I have described the visit to diviners as accurately as possible and the reverence, awe, and respect accorded to them in ancient Igbo land, as well as to priests described in chapter 12 of the novel.

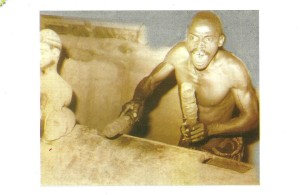

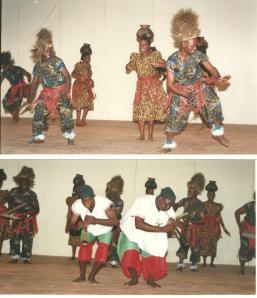

The age grade system, the system of government, double-descent system—matrilineal clans, the patrilineal groups, the omume title-taking ceremonies, ogo, obu, initiation into Egbele Ogo and the description of the villages in different chapters of the book is true of Afikpo, an Igbo town situated in present day Ebonyi State, in the southeastern state of Nigeria.

However, in Omezue, the Complete Achiever, the founder of Uwa was called Isiali, which was not the name of the founder of Afikpo. The description of the land, its people, and the hazards on the highways at the time as described in different chapters were accurately depicted—slave fairs did exist then in some parts of Igbo land, while the salt pits are still there and the taboos still observed as described in chapter 9. The description of the nineteenth century shrine of an Igbo oracle was accurately depicted in chapter 18.

Sources

The cultural component of the book, which is based on Afikpo culture, was from my earlier works and field notes, aided by my intimate knowledge of the people. Other sources are:

Phoebe Ottenberg, “The Afikpo Ibo of Eastern Nigeria” in Peoples of Africa, Abridged,

edited by James Lowell Gibbs Jr.

Simon Ottenberg, Double Descent in an African Society: The Afikpo Village-Group,

(Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1968).

Simon Ottenberg, Leadership and Authority in an African Society: The Afikpo Village-Group

(Seattle & London 1981).

Simon Ottenberg, Masked Rituals of Afikpo (Seattle & London 1970).

Ralph Oko Aja, A History of Afikpo Circa 1600;

Captain Waddington, Intelligence Report on the Afikpo Village Group, (Enugu:

National Archives, 1931).

AFDIST OG. 317 Volume 2, Afikpo Division: Afikpo Clan Social Organization, (1936–37, 1941–42).

For those who might want to learn more about Igbo land and the transatlantic slave trade era in Igbo land, I recommend:

Afigbo, A. E., “Igbo land Before 1800,” Groundwork of Nigerian History,

edited by Professor Obaro Ikime, published by Historical Society of Nigeria,

by Heinemann Educational Books (Nigeria) Ltd.

Ade Ajayi, J. F., and Okon Uya, Slavery and Slave Trade in Nigeria: From Earliest Times to the Nineteenth

Century, (Safari Books Ltd, Ibadan, 2010).

Elizabeth Isichei, A History of the Igbo People (London: 1976).

Elizabeth Isichei, Igbo Worlds: An Anthology of Oral Histories and Historical Descriptions

(London: Macmillan, 1977).

West Africa Study Course, History of West Africa 1000–1970, Book One,

(Channel Islands: Educational Publishing, 1988);

S. N. Nwabara, Iboland: A Century of Contact with Britain 1860–1960 (London, 1977).

UNESCO International Scientific Committee publications—namely,

The African Slave Trade from the Fifteenth to Nineteenth Century.

UNESCO International Scientific Committee, History.

UNESCO International Scientific Committee, UNESCO Studies and Documents—General History of

Africa.

Internet: mhtml: file://C:User\Admin\Documents\Atlantic slave trade–Wikipedia,

the free encyclopedia.